World Test Championship final: Analyzing India’s bowling cartel

The sight of Virat Kohli urging Indian fans in the stands to hype up the bowler running in has become commonplace. It gets the crowd going, breathes life into a possibly dull period of play, and makes the batsman’s job much more difficult than it already is. That is not all though. This act of the Indian captain also signifies something greater, something Indian cricket has not seen before: the presence of a world-class, all-round bowling attack which can out-bowl any opposition, in any condition.

While Indian teams of the past have had legendary bowlers, none have had legendary bowling attacks. And that is what makes the one they have now, special. With the World Test Championship Final approaching slowly but steadily, let’s do a deep dive into how India’s bowling cartel has operated in the last 5 years in Test cricket.

For the sake of this article, we will be looking at the numbers of the seven Indian bowlers from the current squad who have played the most amount of Test cricket in the last five years — Ishant Sharma, Ravichandran Ashwin, Ravindra Jadeja, Jasprit Bumrah, Mohammed Shami, Umesh Yadav, and Mohammed Siraj. We’ll be looking at their overall numbers as well as numbers in England and New Zealand combined, considering the conditions in those countries are the closest to what the conditions for the WTC Final are going to be.

To start off with, the supremacy of India’s bowling can be very simply quantified by the following numbers. In the last 5 years in Test cricket, India have taken 973 wickets, second most after England who have taken 140 wickets more in 14 more matches. Their bowling average of 24.84 is the best in this period among all Test playing nations, followed by South Africa who average 2.26 runs more per wicket. That is a pretty big gulf. India’s overall Economy Rate of 2.87 and Strike Rate of 51.8 are the best and second best too respectively, while Indian bowlers have also taken 43 five-wicket hauls in this period, 5 more than the next best, England. And if that was not enough, the highest wicket taker in this period has also been an Indian- Ravichandran Ashwin, with 233 wickets.

Now that we have established how good India’s bowling attack as a whole has been, let’s take a look at some of the most important cogs of this wheel. Fig 1 shows the number of wickets taken and bowling averages while Fig 2 shows the Strike Rates, Economy Rates, and Balls Per Boundary of the seven Indian bowlers mentioned above, innings-wise, in the last 5 years overall, and in England and New Zealand combined. The general trend you’d expect to see is fast bowlers having more wickets in the first innings, and spinners having more wickets in the second innings as the pitches crumble and become more conducive to spin bowling. While Ishant, Bumrah, Umesh, and Jadeja satisfy that trend, the opposite has been true for Shami, Ashwin , and Siraj.

Fig 1: Wickets Taken and Bowling Averages of Indian bowlers innings-wise in the last 5 years overall and in England and New Zealand combined.

We have often heard the moniker of ‘Second Innings Shami’ being given to Mohammed Shami. You can see why in Fig 1. He has more wickets in the second innings in the last 5 years than in the first innings, and his average dips by a whopping 35.7% in the second innings. While him and the Indian team would both want better consistency in the early stages of the game, his destructive ability of closing out games has been second to none. His average of 19.29 in the second innings in the last 5 years is the second best after Pat Cummins’ 18.49, and his Strike Rate of 36.65 is also the second best after Kagiso Rabada’s 36.3.

Ashwin meanwhile, surprisingly has more wickets in the first innings than in the second. This firmly proves his credentials as an all conditions bowler. He has not only been effective in spinning webs around opposition batsmen on the 4th and 5th day pitches, he has been an attacking option in the first innings as well. To put things in perspective as to how good this bowling attack as a whole has been, look at the following numbers :

- 30.44 — Average of Right Arm Pacers in Last 5 years in 1st innings

- 25.50 — Average of Right Arm Pacers in Last 5 years in 2nd innings

- 41.03 — Average of Right Arm Spinners in Last 5 years in 1st innings

- 30.26 — Average of Right Arm Spinners in Last 5 years in 2nd innings

- 36.88 — Average of Left Arm Spinners in Last 5 years in 1st innings

- 24.16 — Average of Left Arm Spinners in Last 5 years in 2nd innings

Except Siraj’s first innings average, all other bowlers have overall averages less than the overall average for bowlers of their respective bowling style in the last 5 years. And Siraj is only 5 Test matches old.

While the overall numbers of every bowler in this list have been extraordinary, they do take somewhat of a hit in England and New Zealand. Ishant is the only bowler who has similar or better returns in those conditions than his overall returns. The biggest concerns have been Shami’s hugely under-whelming numbers (average of 36.5 and 42, and economy rate of 3.48 and 3.92 in the first and second innings respectively), and Ashwin and Jadeja’s inability to pick wickets at a decent rate in the second innings. Ashwin’s average and strike rate (first row of Fig 2) jump to 37.4 and 97.2 respectively, while Jadeja’s average and strike rate jumps to 67.67 and 104 respectively.

Although there are obvious areas of improvement for Indian bowlers in English conditions, they don’t need to lose sleep over it. Ashwin and Jadeja are bowling better than they have ever bowled. And CricViz put out an article recently where they showed how frustratingly unlucky Shami was in the 2018 series against England. Unless they suddenly forget how to grip the ball, they should be fine.

Fig 2: Strike Rate, Economy Rate, & Balls Per Boundary of Indian bowlers in the last 5 years in Test cricket (1st innings vs 2nd innings).

Fig 3 and Fig 4 show the wickets taken, bowling average, strike rate, economy rate, and balls per boundary of Indian bowlers against Left Handed Batsmen(LHB) and Right Handed Batsmen(RHB). There are several interesting things to note here.

- Ishant loves bowling to LHB in helpful conditions. His average against LHB dips by more than 6 runs while his average against RHB increases by more than 3 runs in England and New Zealand. There’s a catch to this though. This doesn’t necessarily mean he struggles against RHB. His strike rate against RHB is far better than that against LHB in England and New Zealand, but he concedes runs at a much higher clip, 3.58 against RHB compared to 2.38 against LHB. While on one hand he ties left handers up in knots with his round the wicket angle, on the other, he picks the wickets of right handers for fun, while going for a few extra runs because of his straight lines.

- Bumrah averages less than 20 against RHB in his career, which only rises to 21 in England and New Zealand. He’s a tormentor of right handed batsmen.

![Fig 3: Wickets taken and Bowling Average of Indian bowlers in last 5 years in Test cricket (Left handed batsmen[LHB] vs Right Handed Batsmen[RHB]), India's bowling cartel](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/1500/1*m8QwTkyaigzqTnNTKiHgEw.png)

Fig 3: Wickets taken and Bowling Average of Indian bowlers in last 5 years in Test cricket (Left handed batsmen[LHB] vs Right Handed Batsmen[RHB]).

- Shami is a nightmare for LHB. He too, like Ishant, adopts the round the wicket angle to great effect. He averages less against LHB both overall and in England and New Zealand. His strike rates are also considerably better against LHB, and his biggest problem, the occasional boundary ball, also gets solved to a certain extent, as his economy rate and balls per boundary, both stand at a decent 2.98 and 13.53 respectively against LHB. Its against the RHB that he struggles in conditions which demand discipline, as can be seen by his economy rate of 4.06 in England and New Zealand (Fig 4).

- Ashwin can get LHB out in his sleep. His average against LHB has been 20 overall, and even lower in England and New Zealand. He not only gets them out, he doesn’t let them score as well, conceding only 2.37 rpo overall and 2.05 in England and New Zealand. Left handed batsmen have only hit a boundary every 5 overs against Ashwin in England and New Zealand in the last five years. One boundary, every five overs. You’d take that from your lead spinner in conditions that are not tailor made for spin bowling any day. The only blip in his record has been his insanely high average and strike rate against RHB in those conditions. He recently had one of his best series outside the sub-continent though in Australia, where he had the better of the greatest RHB in Test cricket currently, Steve Smith.

- Jadeja’s overall record in the last five years suggests he is equally adept at bowling to RHB and LHB. Although he average slightly more against LHB, that’s because his economy rate against them is slightly more as compared to against RHB, understandably so. His strike rate in fact, is better against LHB than against RHB overall. This changes massively in alien conditions though. He has surprisingly given runs at 3.87 rpo against RHB in England and New Zealand. Although still doing a job, he no longer remains the bank in those conditions that he is otherwise.

![Fig 4: Strike Rate, Economy Rate, & Balls Per Boundary of Indian bowlers in last 5 years in Test cricket (Left handed batsmen[LHB] vs Right Handed Batsmen[RHB]), India's Bowling Cartel](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/1500/1*Y7kr15Xeh7sfxojro3LK_A.png)

Fig 4: Strike Rate, Economy Rate, & Balls Per Boundary of Indian bowlers in last 5 years in Test cricket (Left handed batsmen[LHB] vs Right Handed Batsmen[RHB]).

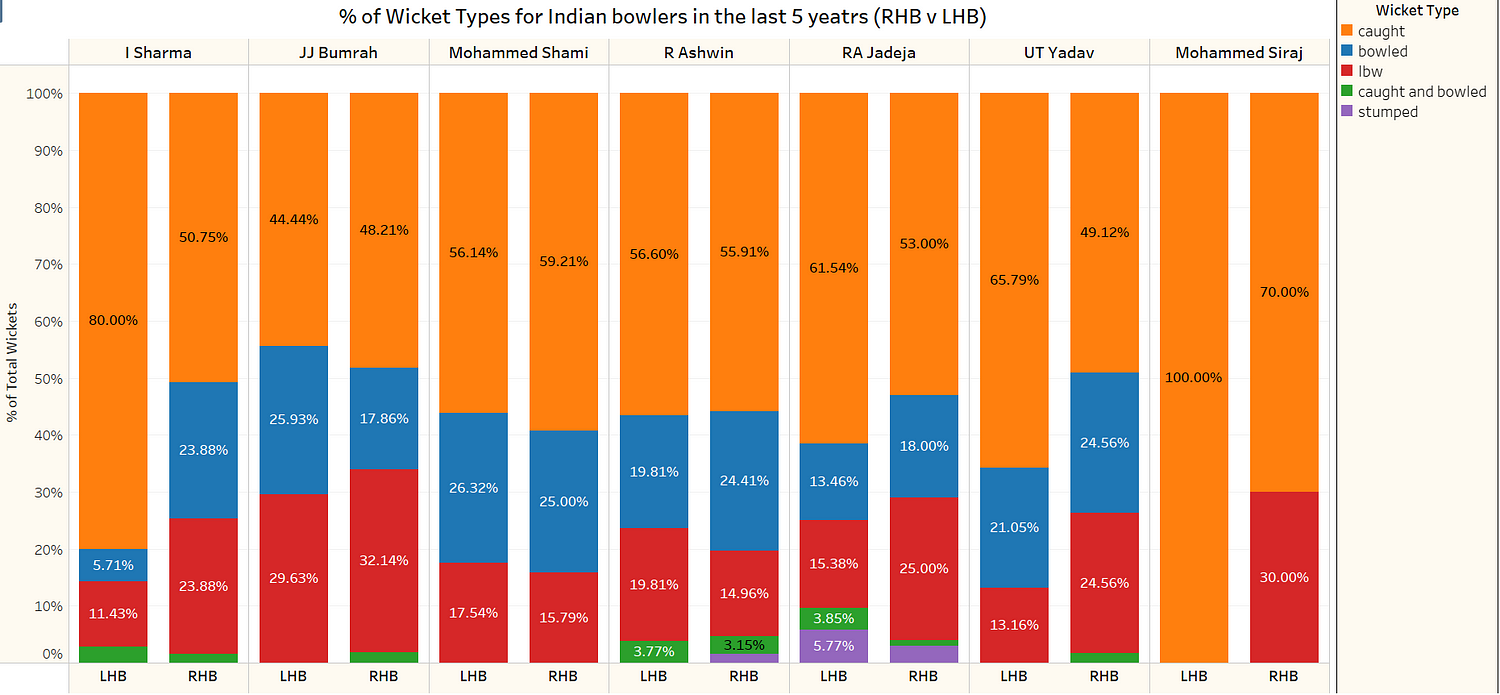

Now that we have seen how the Indian bowlers fare against left handed and right handed batsmen, let’s take a look at how they have taken their wickets against them in the last five years. Fig 5 shows the percentage of types of wickets taken by Indian bowlers against RHB and LHB in the last 5 years in Test cricket.

The most striking observation from this is Bumrah’s extraordinarily high Bowled+LBW percentage. More than half of his wickets have come in the form of bowled or LBW against both LHB and RHB. Among New Zealand’s batsmen, Tom Blundell, Mitchell Santner, Henry Nicholls, BJ Watling, and Ross Taylor have bowled+ LBW percentages ranging from very high to moderately high. Don’t be surprised if you see Bumrah gunning for their pads and uprooting a few stumps in the process in the WTC Final.

Another interesting observation here is the striking difference in the percentages of bowled and LBW against RHB and LHB for Ishant. Whilst less than 20% of his dismissals against LHB have been bowled or LBW, almost half of them have been bowled or LBW against RHB. The explanation for this is obvious. Ishant naturally brings the ball into the right hander and takes it away from the left hander. His round the wicket tactic against LHB, bringing the ball in with the angle and then swinging it away, has been a trademark of his over the last few years. With both of New Zealand’s first choice openers being left handers, expect Ishant to keep them on their toes and keep Rishabh Pant and the slips busy, while also potentially troubling Ross Taylor, who is a LBW candidate.

Shami’s generally straight line of attack, coupled with his reverse-swing abilities mean he too has a substantial portion (>40%) of his wickets in the form of bowled or LBW. Umesh’s case is interesting. While he is a natural outswing bowler, almost half of his wickets against RHB in the last five years are bowled or LBW. This is because he has been used mostly in Indian conditions, where reverse-swing plays a key role and Umesh has been one of if not the best exponent of it.

Jadeja and Ashwin’s numbers against RHB and LHB respectively show that they attack both edges of the bat consistently. While Jadeja has been almost like a machine, bowling in one spot with the natural variation making some balls turn and some balls skid straight on, Ashwin has been like a scientist, doing all sorts of experiments, and keeping left handers in his pockets. New Zealand can potentially have 5 left handers in their XI for the WTC Final. Ashwin becomes the first line of attack for India in that case.

Fig 5: Percentage of different types of wickets against RHB and LHB for Indian bowlers in the last 5 years in Test cricket.

To cap off the analysis, let’s look at which batsmen have been dismissed the most by these Indian bowlers in the last five years. Fig 6 shows the top 5 victims of each Indian bowler in the last five years in Test cricket.

Enough has already been said about Ashwin’s brilliance. This final chart only adds to it. Four of Ashwin’s top 5 victims have been Steve Smith, Joe Root, Alastair Cook, and Ben Stokes. That is an elite company and Ashwin has had the better of them, consistently. The top 5 victims of Jadeja and Ishant are all proper batsmen, while those of Bumrah, Shami, and Umesh include both top order bats as well as tailenders.

Fig 6: Top 5 victims of Indian bowlers in the last 5 years in Test cricket.

With the WTC Final only about a week away, the hype is slowly starting to build up to a crescendo. Although the current plan is to only allow around 4000 spectators at the Ageas Bowl for the final, that number is by far better than 0. And although the noise generated by them won’t exactly feel the same as the noise generated by 60,000 people at the Eden Gardens, nonetheless you can expect Kohli to rile up the Indian contingent among them as any one of the hitmen of the Indian bowling cartel run in to bowl.